Recently, a friend and colleague asked me to share more in-depth details about my outlining process, so here goes. 🙂

I’m what they call a plotser, meaning I do a mix of plotting and pantsing when I write. Plotting suggests that I outline what’s going to happen (plot, character arcs, etc.) and pantsing suggests that I write “by the seat of my pants” without any outlines.

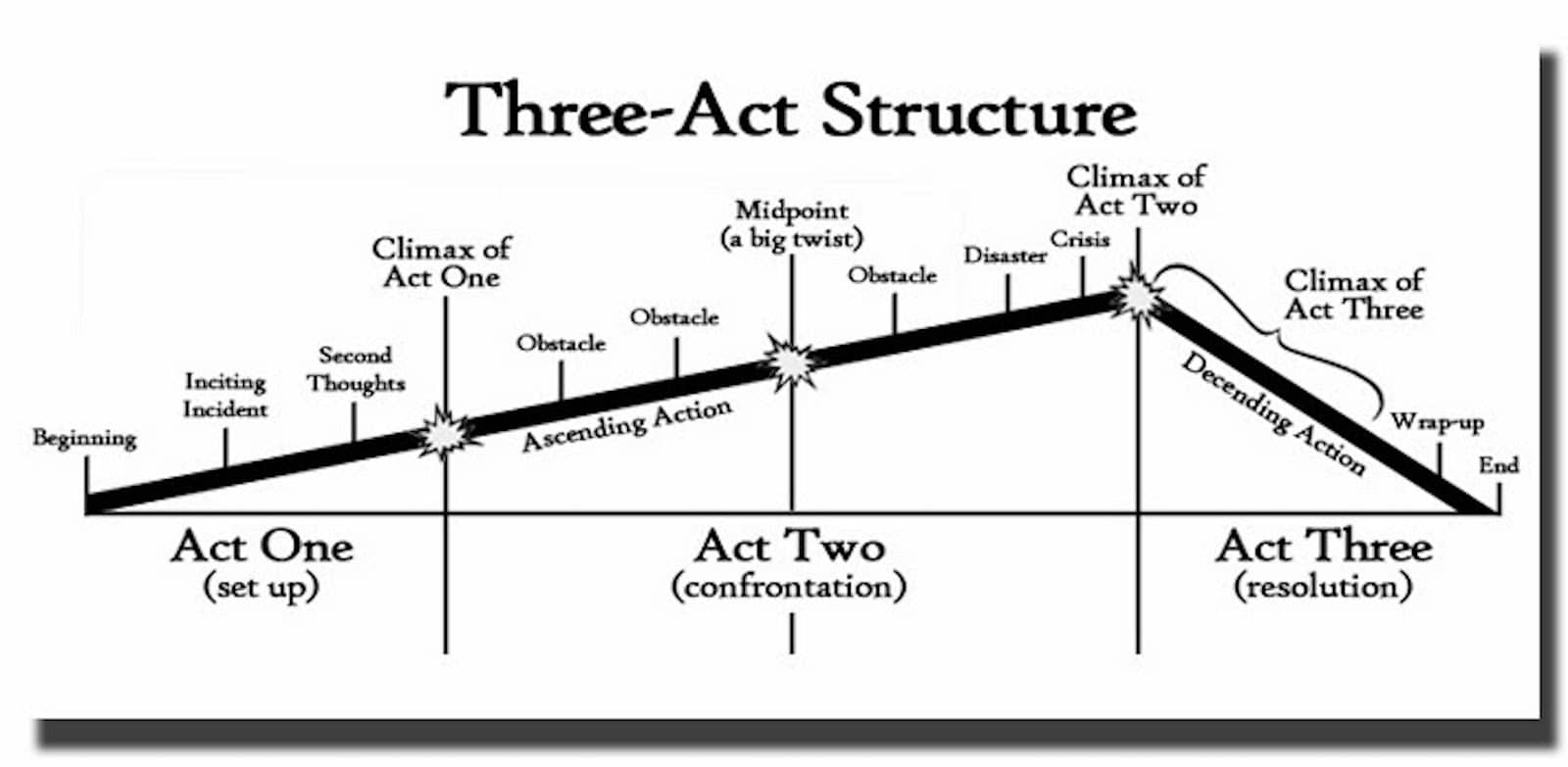

THREE-ACT STORY STRUCTURE

When I outline, I usually use a three act story structure, meaning I outline the major themes/arcs/events for a book of three acts. There are tons of other structures like the Five Act Structure, Snowflake Method, Circle Structure, etc. The idea is to find a way of dividing the story that works best for you. Try out a bunch of them and experiment. (You can see the Three Act one at the top of this blog post. You can also read more about the Three Act Story Structure here: http://www.writers-for-writers.com/2017/11/08/structure-lesson-2-three-act-structure/)

Inside each of those acts, I will also use the scene and sequel method to insure proper pacing of major scenes. (You can read more about this in the article I wrote on it here: https://writershelpingwriters.net/2015/01/writing-patterns-fiction-scene-sequel/) Most books use scene and sequel, even if they aren’t aware of it. In the article I wrote and linked to, I use Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol to demonstrate it. After reading about it, try it out with something you love like Star Wars: A New Hope or Dune.

When outlining major scenes in the acts, I use either physical 3×5 notecards or I use the notecards in Scrivener (my writing software). Usually, my ideas come to me with a few scenes fleshed out. I know how the story will begin and end. Sometimes I know bits of the middle, too. I choose to outline backwards because it helps me know where I’m going. For example, let’s say the story ends with two characters flying away from Earth in a busted up ship. I then ask myself, “What busted up the ship? What needs to happen for these characters to get together and fly away in this ship?”

The answers to those questions become a scene or several scenes in the outline. Let’s say the ship is damaged in a big climatic battle where both characters were fighting the big bad. Then I’ll ask, “What was the big battle about? Why were they fighting the big bad? Who is the big bad? Where was this fight?” All of these questions give me more info, and I can keep going backwards and asking more questions. (Obviously you’d want more details than this but this is only an example in this post.)

Doing this ensures I have less of a muddy middle than if I were going forwards. It also ensures that every scene I’m adding is directly tied to the plot or character arcs. Every scene will push the story forward. It also ensures that I’m always writing with the end in mind because of how I set the scenes up (going in reverse). Some people prefer to outline forwards and that’s fine—do what works best for you—but for me, this works best.

ZERO DRAFTING & THE FIRST DRAFT

Once I have my outline, I start fleshing out scenes until I have a loose zero-draft. I call it a zero-draft because it’s more of a fleshed-out outline than a story. It’ll have bits of dialogue, descriptions, action, whatever pops in my head as I read through my outline. After I take my outline to a 20-40K zero draft, then it’s time for me to write the full draft. (You can read more about zero-drafting here: https://chelseapenningtonauthor.com/what-is-zero-drafting/ )

This is where my pantsing comes in. My outline and zero-draft tend to focus on major plot and character points. Now it’s time to fill in the in-between bits of getting from here to there as well as fleshing out each scene, ensuring that there’s enough description to show setting, characters, motivations, etc. I don’t usually outline this as I let the story or the characters lead me where they will to get to the next scene. Occasionally, the scenes don’t meet. I might need another scene in between, or maybe I need to flesh out what I’ve written even more. But sometimes I end off somewhere in left field, and my outline has to shift to accommodate. Someone who’s a plotter, would see this as a problem. Pantsers love this though as it can open up the plot and reveal necessary scenes that enrich the original idea. But sometimes that field is a muddy swamp I should’ve never walked into, and then I need to backtrack and cut scenes.

For me, a lot of this depends upon the story. Some are well thought out in my mind and outlined enough that detours aren’t a huge deal, but sometimes, if I don’t think through something in the plot enough, characters will lead me on a wild goose chase. Because I’m both plotter and pantser, I can usually make it work.

REVISING TO THE FINAL DRAFT

After the fleshing out and development of the first draft, I set the novel aside for a week and return to it with a fresher, clearer mind. I call this time my “percolating” time. It distances me from the story in such a way that I can approach it wearing my editor hat vs. my writer/author hat, but it also allows the story to float around in my unconscious and often conscious brain. Sometimes that’s where I find the plot holes or areas where I didn’t wrap up a plot arc properly. My brain gets to ruminate on everything and suggest changes or additions to me.

At this point, I read through it and revise as needed. I also do consistency checks from the book or series bible, making sure that blue-eyed character X has blue eyes throughout or that I am consistent with character X’s voice. Then I’ll put aside the manuscript for another week (more percolating) and come back to it, ready with my ear phones. I have Scrivener (my writing program) read the book out loud to me. Because it’s a computer reading the novel (vs. me), I’ll find errors like using the wrong word (e.g. where vs. were) or wrong spelling. Part of the importance of the novel being read to me is that the computer doesn’t auto-correct what I’ve written the way my brain does. After hearing the story, I’ll read the text myself out loud to find grammar, spelling, and mechanical errors.

After those corrections and any final-ish changes, the book goes to my alpha and beta readers before finally going to the editor(s) and so on as it gets ready for publication. Of course, changes will still be made after that, but usually not large ones. Finally, the book gets published and off it goes into the world!

And that’s my process.